Author, The Dvorak Keyboard and This is True

The Dvorak keyboard is an ergonomic alternative to the layout commonly found on typewriters and computers known as “Qwerty”. The Qwerty keyboard was designed in the 1870s to accommodate the slow mechanical movement of early typewriters. When it was designed, touch typing literally hadn’t even been thought of yet! It’s hardly an efficient design for today’s use.

The Dvorak keyboard is an ergonomic alternative to the layout commonly found on typewriters and computers known as “Qwerty”. The Qwerty keyboard was designed in the 1870s to accommodate the slow mechanical movement of early typewriters. When it was designed, touch typing literally hadn’t even been thought of yet! It’s hardly an efficient design for today’s use.

In contrast, the Dvorak (pronounced “duh-VOR-ack”, not like the Czech composer) keyboard was designed with emphasis on typist comfort, high productivity and ease of learning — it’s much easier to learn.

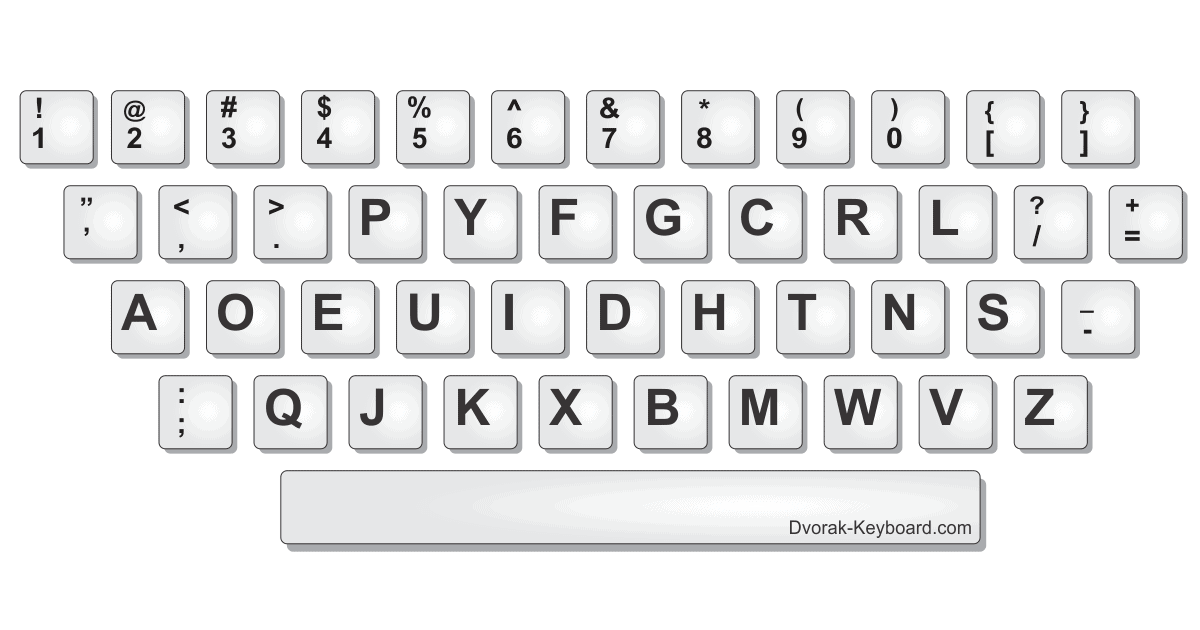

There were several variations in the Dvorak’s design in its first few decades, but these were settled when the American National Standards Institute approved a standard for the layout of the Dvorak in 1982. The diagram above shows that standard layout as adapted for computer use.

Because computer-based research wasn’t even a researcher’s dream in the late 1920s and 30s, the Dvorak design took about 12 years to perfect, and included extensive study of languages using the Roman alphabet (mostly English), the physiology of the hand, and practical studies.

Dr. Dvorak (Univ. of Washington, Seattle; he lived 1894–1975) used his research to design two other keyboards specifically for people with only one hand (one each for the right and left), which allow people with the use of just one hand to type very easily and efficiently — at speeds up to 50 wpm.

Why Is Dvorak Easier to Learn?

The Dvorak layout has the most-used consonants on the right side of the home row, and the vowels on the left side of the home row. Among other design features, it is set up to facilitate keying in a back-and-forth motion — (right hand, then left hand, then right, etc.) The back-and-forth flow obviously makes typing quicker and easier: try typing the word “minimum” on the Qwerty keyboard, then look how you’d type it on Dvorak.

When the same hand has to be used for more than one letter in a row (e.g., the common t-h), it is designed not only to use different fingers when possible (to make keying quicker and easier), but also to progress from the outer fingers to the inner fingers (“inboard stroke flow”) — it’s easier to drum your fingers this way (try it on a tabletop).

The Dvorak design puts fully 70 percent of all English keystrokes on the home row (only 32 percent of Qwerty’s are on the home row), making Dvorak much easier, faster, and — probably (no formal studies have been done as yet, but anecdotal evidence supports it) — less likely to result in carpal tunnel syndrome and other repetitive motion injuries.

Remember when you took typing classes, probably in high school? You got to do drills with such “words” as “fff”, “jjj”, and “jkl;” — why practice such specific nonsense that you will never actually type? Added to the awkward physical motions Qwerty requires, these nonsense words are counter-intuitive, making Qwerty very hard to learn. On Dvorak, the keys on the home row alone make up literally thousands of words (we have a list of nearly 5000 from one electronic dictionary alone!), meaning you could have typed real words on your first day of typing class …if you had learned on a Dvorak keyboard.

The row above the home row contains the next-most-used letters and punctuation. Why? Because it is easier for your fingers to reach up on the keyboard than down. What’s left are the least-used keys, which are obviously relegated to the bottom row.

Should We Switch?

Even if you don’t want to switch (it’s actually fairly easy — I did it in college, and my typing speed went from 50 WPM to over 100), why the heck are we forcing children to learn the draconian ergonomic failure “Qwerty” when there’s a such a good alternative available?

Why teach kids for weeks and weeks and weeks to master a complex skill when in two or three weeks they could learn Dvorak, and then get on with what they’re at the keyboard to do! Writing, programming …creating!

If it’s so good, why isn’t everyone using it? Clearly, a good question. There are a lot of reasons for it, and they are too numerous and complicated to explain fully here (they are fully explained in my book The Dvorak Keyboard). Mainly, the Qwerty keyboard became entrenched in tradition. By the time Dr. Dvorak came up with his design, there were hundreds of thousands of typewriters, and it would have cost millions to convert them all over.

Yet the benefits were so obvious that the switch was just about to be made, but then World War II broke out, and the War Dept. ordered all typewriter keyboards be set to the most-common standard: Qwerty. Typewriter manufacturers, meanwhile, retooled to produce small arms. By the end of the war, Qwerty was cast in concrete.

Then Add Discrimination!?!

Unbelievably, there are people with personal vendettas against the Dvorak. In 1956, a U.S. government researcher published an astoundingly biased “study” that railed against the Dvorak layout. When other researchers found the conclusions suspicious, they asked to see the raw data — but the government researcher had destroyed it all! Yet the anti-Dvorak still point to the “study” by the General Services Administration as “proof” that there’s something wrong with the Dvorak. But their “evidence” doesn’t even exist.

Such vendettas exist now, too. The most commonly quoted anti-Dvorak screed over the past few years is one by Stan Liebowitz and Stephen Margolis. I responded to that one way back in 1995 (copy of that here).

Certainly, people are using it. How many? It’s impossible to know: unlike typewriters, which needed precision mechanical work to convert them, computers are by their nature programmable, and it’s a cinch to convert them to Dvorak. So how many people have actually done that? The only way to really find out is to do an expensive controlled survey, and no one is rushing forth with the money to fund such a study.

To learn more about the Dvorak layout, I recommend two levels of information. Browse through my Dvorak Research Materials linked below for what you want to know. For the ultimate design reference, ThisIsTrue.Inc (my publishing company) is the exclusive distributor of Typewriting Behavior, Dr. Dvorak’s 546-page book on the keyboard’s research and design — it’s a classic! The book was printed in 1936, and there will never be any more. I have a quaint 1936 review of the book.

Author Randy Cassingham is best known as the creator of This is True, the oldest entertainment feature on the Internet: it has been running weekly by email subscription since early 1994. True is social commentary using weird news as its vehicle so it’s fun to read. Click here for a subscribe form — basic subscriptions are free.